Notes from the Jabour School

Multidimensional harmonic models for improvisation, composition and arrangement from Hermeto Pascoalʼs Grupo in Rio de Janeiro

Jovino and Hermeto backstage at Blue Note New York, 1991. Photo by Tim Geaney

Harmony is the Mother, Rhythm is the Father and Melody is the Offspring

-Hermeto Pascoal

My first 15 years as a full-time musician were spent in Hermeto Pascoalʼs Grupo in Rio de Janeiro. This ensemble was the core of what became known as ‘The Jabour Schoolʼ, named after the neighborhood in Rio where Hermeto and all the musicians in his ensemble lived in the 1980s and 1990s. I was the pianist, flutist, record producer and road manager for the band. The experience of intense rehearsals for 30 hours each week, plus the hundreds of concerts and recordings we did together, allowed myself and my colleagues (Itiberê Zwarg (bass), Carlos Malta (woodwinds), Marcio Bahia (drums), and brothers Pernambuco and Fabio Pascoal (percussion)) a direct pathway to the self-taught and intuitive musical genius of Hermeto, and to observe how he conceived and explained to us the musical entities of harmony, melody and rhythm, in addition to being a consummate artist on piano, flute, saxes and a wide variety of artisanal instruments, such as kettles, tubes, sewing machines and much more. In our rehearsals and concerts, we also witnessed how Hermeto would use different methods to describe a single musical concept to the six musicians of our ensemble, each of whom with different musical backgrounds and training. During those years with Hermeto I learned practical ideas which shaped my own musical growth which I hope I can use to inspire others. In this article I will describe the basics of Hermetoʼs universal approach to harmony, with some practical ideas for individual development of the harmonic sense.

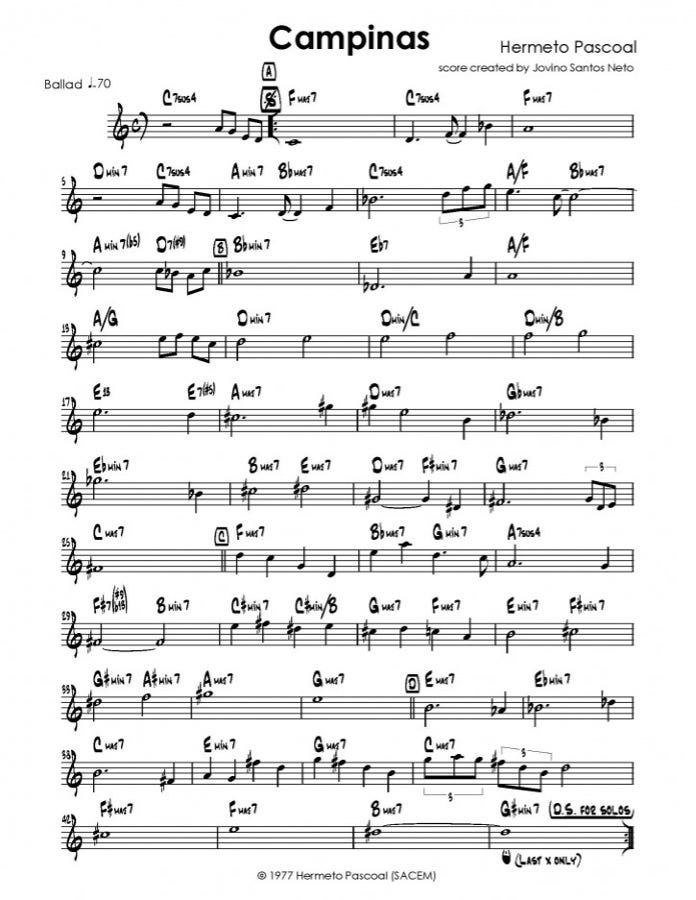

On the first day I met Hermeto in 1977, he gave me a sheet of music paper with written chord symbols. Those were the changes to his theme Campinas:

Over the course of several years, this piece was used almost on a daily basis as the material over which we practiced the art of improvisation. The first thing that Hermeto taught us when improvising over chords to ‘Campinasʼ was to write above each chord symbol a number of triad options. So, if a chord was a C major 7th, we would write the symbols for G, E minor, D and B minor. These triads are components of the C Lydian mode. If a chord was a C minor 7th, we would write the triads Eb, Bb, D minor, F. These are components of the C Dorian mode. For each chord type there are between 2 and 5 triad options to be explored.

However, instead of having us learn linear scales and modes, Hermeto would inspire us to create simple, intuitive melodies based on those triads. He also remarked that there was not a simple hierarchy of triads, no sequence or order of importance. So, we could be playing an E minor or a D major melody over the C major chord, which blurred the more traditional aspects of the harmony, in which hierarchy is a given premise.

For me, with a then limited knowledge of music theory and hardly any experience improvising over chord changes, this was a completely new approach. It meant I did not have to engage in linear thought processes, leaving space for my intuition to operate while dealing with simple melodic figures. Prior to joining Hermetoʼs Grupo, I had studied biology and was accustomed to the logical, Cartesian approach of the scientific method.

Learning music with Hermeto and the Grupo proved to be one of my biggest challenges to overcome. Over time, the members of our ensemble became so familiar with this concept that we no longer had to write the triad options over the chords. The whole process became instantaneous and directly connected to the quick flash of reflex. Not the automatic, mindless reflex of habit, but the mindful, creative reaction that came to us organically when moving over a changing harmonic landscape. Hermetoʼs harmonic language that he used in his compositions, arrangements and improvisations provided us with ample material with which to practice. His use of chord progressions was always inspiring, surprising and innovative.

After moving to the US in 1993, I saw how most schools and music instruction books focus almost exclusively on the linear approaches of scales and modes as gateways to improvisation. These approaches tend to result, in my opinion, in mechanical solos that fail to connect with a musicianʼs intuition. What I hear is a lifeless and flat flow of notes without melodic coherence. Traditional harmonic studies often describe wide intervals, such as ninths, elevenths and thirteenths, but if intervals can be imagined in orbital shapes rather than linear distances, we can then visualize the same long intervals as inversions of shorter steps, which come in pairs: second/seventh, fourth/fifth, third/sixth. This system brings the intuitive perception of intervals and chords to exist within the human hand, without the need for any quantity greater than five. We use our hands to play instruments, and it is intuitively possible to connect our 10 fingers as interval and chord builders, even if you are playing a melodic instrument.

The way to harmonic conscience is built on intuitive major and minor triads. They exist in our mindʼs ear as gestures and notations which have voices, just as easily recognized as the voices of our friends and family. Even though we tend to treat chords as individual entities or motionless objects, in reality they connect to and inform all the musical material surrounding them, so it would be more appropriate to consider chords as verbs, (which denote actions), rather than nouns, which denote objects. We can then visualize any chord as a cloud of possible musical actions, with an ‘atmosphereʼ of triads surrounding it. I found it convenient to use three dimensional images as a visual aid to enable the multi-sensorial perception of harmony.

Music, being the art of placing sounds over time, is of course a four- dimensional sensory experience for both musicians and listeners, but the point is that, by employing three-dimensional objects as images of reference, we are one dimension away from the flowing nature of the musical experience, rather than the two-dimensional degrees that separate the linear objects of scales, modes and arpeggios from the immersive musical universe. Furthermore, I find that even better than using abstract Platonic solids as sources of imagery for musical reference, we can instead focus on shapes commonly found in Nature. Trees, for instance, can very effective models for conceiving harmonic entities. As land-dwelling beings, we think of trees as stationary objects, but somewhere in the inner core of our brains, we can still visualize trees as stations along a pathway of travel like our canopy-dwelling ancestors.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Jovino Santos Neto - Writing from the Heart of Music to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.